|

|

||

|

www.radioseagull.co.uk |

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

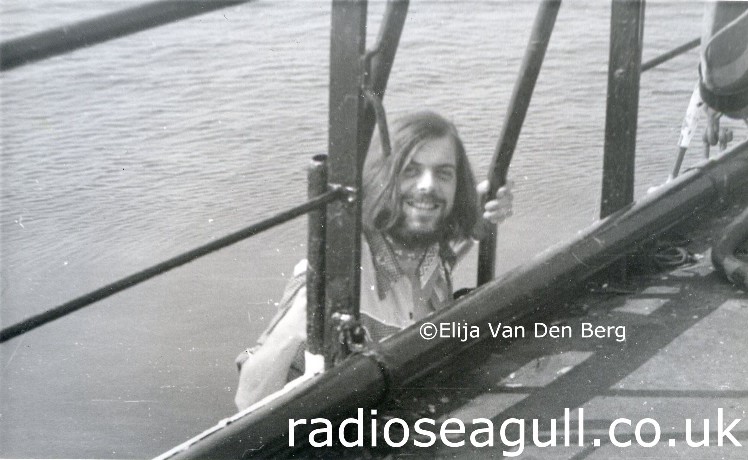

Elija Van Den

Berg: "My opinion

of Radio Seagull (onboard the MV Mi Amigo in 1973/74) is it is the closest to a perfect radio station I have ever

heard. The discussions and presentation of the programmes were human and

intelligent. There was a real feeling of warmth and compassion. People

talked about issues in a calm manner to people rather than shouting AT

them, which is mostly what they do today (no communication between

listener and broadcaster/DJ. There was real feedback from the listeners,

which was frequent and created real debate and thought. I was there all

that period and it is nice to get some kind of acknowledgement of my

existence after all these years..." |

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

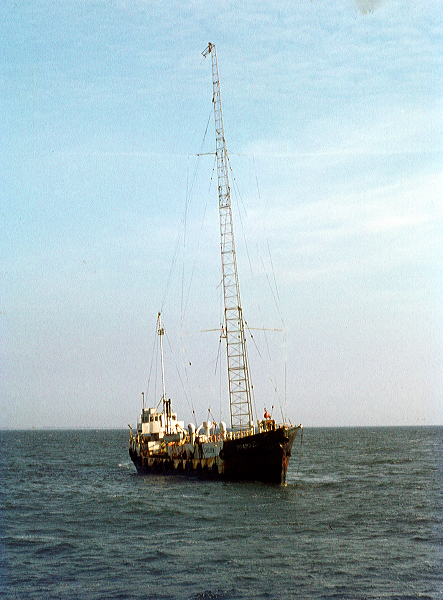

1973: Barry Everitt, photograph from the personal archive of Elija Van Den Berg |

||

|

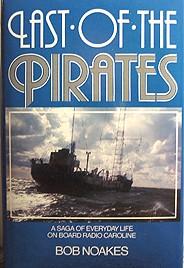

Of particular interest is Bob Noakes description of Hugh Nolan and Barry Everitt during their

time on board the Mi Amigo, anchored in the International waters of the

North Sea. Three years had passed since the demise of Radio Geronimo (with

studios in Harley Street, London, W1 - broadcast via Radio Monte

Carlo). Hugh and Barry, appeared on board the Mi Amigo at the request

of, and with the full support of Ronan

O'Rahilly, owner of |

||

|

Bob Noakes, 1984. Last Of The Pirates ISBN 0 86228 092 3 |

||

|

|

||

|

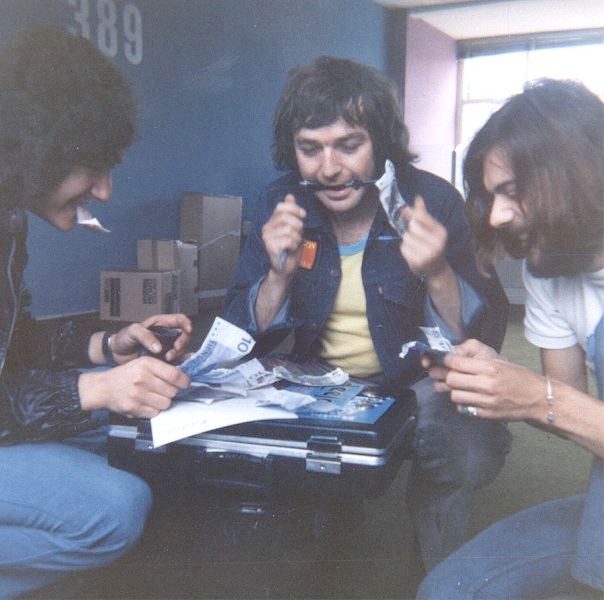

"...Hugh and Barry arrived with their hash pipes and crates of underground records, and above all, with the total blessing of Ronan who had sent them across to us.... ...Radio Seagull had become established. I was to spend the next few weeks on board in the company of some very strange people who were operating what had become possibly the strangest radio station in Europe. Our two new djs had given the station a distinctive new ultra-progressive sound that I found neither good nor bad - I simply didn't understand it. Andy and Johnny were on land enjoying a break, which left the station largely in their hands. As there was still nobody in charge to make decisions of music policy and direct the station's output, and love and peace, hash smoke and good vibes were guiding us, Radio Seagull soon became self-indulgent, directionless and empty... ...It was a wonderful broadcasting and communication opportunity for all involved; a transmitter which most of Europe could hear and carte-blanche to do and say anything.... ...Barry and Hugh were undoubtedly professional, but their choice of music was so heavy and often so obscure that they could have only been reaching a small percentage of the available audience. The emphasis was on old Dylan tracks with plenty of Zappa and Beefheart. Later in the evening came some of the more horrisant music that only the most erudite of listeners would have been able to understand... ...The emphasis on drugs had also become much greater and this was reflected in the programmes; a special jargon had come into use which some of us could not understand. The station, and everything about it, had become so avant-garde and freaky that it was totally far out... ...Barry and Hugh were night-people who seldom saw the light of the sun. They slept by day and arose at about four in the afternoon to choose records for the evening's programmes. Their breakfast was usually a cup of tea and a thickly rolled joint which provide them with enough lethargy to stagger through their work and get high on the strange and fantastic music they selected...."

|

||

|

Webmaster has a programme with Radio Seagull in 2020

|

||

|

||

|

PRE

AMBLE... Barry Everitt: That's Radio Seagull, yeah, on the Mi Amigo - where my jazz collection still sits (laughter)... in a watertight, in a watertight hold. I remember sealing it, locking it. It was watertight. I reckon they're OK. I reckon in probably about 20 years time those albums will be worth so much that it'll be worth sending a diving team down to get them. I've tipped off my kids so my grandchildren can go down and dig 'em out. There's about, there's about two thousand jazz albums down there, and blues albums, vinyl...

Mark

Dezzani: Before we get onto the Caroline/Seagull thing and Ronan, tell us

about Jimmy Miller. (regarding Radio Geronimo in 1970)

BE: Jimmy

Miller was very much, I mean, he was a back, backroom part of play. He

wasn't really, he wasn't really part, I mean he was the partner with Tony

Secunda. Tony Secunda really was the front man for the organisation. Jimmy

was just doing his things, producing his records - that's what he did -

and he just invested money with Tony in this, in this sort of

entrepreneurial company at 1, Harley Street... and he used to pop in, see

him, we used to go round his house and listen to the new Rolling Stones

record before it came out. Things like that, you know, it was cool, but he

was... and he had a completely manic wife I remember at the time, who was

constantly throwing tv's and records and, "Don't bring those hippes round

here again!" (laughing) But Tony was really the main, the mainstay of the

situation, and as I say, he was managing... there was a band called Balls

- which he managed at the time, who were again regular... Trev Burton and

all that crew were regularly sort of... Alan White, now the Yes drummer,

still the Yes drummer... you know, quite heady times, and then he started

doing T.Rex, and I ended up sort of tour manager, driving for them, having

to change cars every night because the cars would get ripped apart by the

screaming girls, and there was Tony, Tony going round collecting all the

cash and putting it in a big bag. It was really old school, old school

rock and roll. I sort of got a taste for it I guess then. That was gonna

be what I was gonna do. I ended up doing radio for another ten years, but

eventually I got on the road with a band and became a sound engineer as

well.

...I tell you, when you guys first got in touch with me I couldn't believe that there was... I didn't believe there was such interest to be quite honest. (sound problem with mics)... that frustrated me. It was the same with... as a tour manager, I mean, I started off as a sound engineer because I couldn't get work in London. I got back from doing ten years of radio in America and I had to come back because of my daughter. I had a custody... and try and blag as I always used to in America, blag the late night slot and build it, I build up an audience, and of course I went to Capital and they told me to basically bugger off. Very nice, got my CV and demo tapes and history and they said go and work out in the sticks somewhere and when you've got your... then maybe we'll bring you out. I said I can't work in... I've gotta work in London. Anyway, on that CV obviously, was the fact that I'd worked on Mi Amigo, and the Mi Amigo sunk two days later... and they were trying to find djs who'd worked on the Mi Amigo and there was no one in town. Johnnie Walker and crew were all in... still in America. I left Johnnie in San Francisco. He and I used to be on opposition stations together and.... (rustling sounds get worse) ... We've lost sound.

So, where was I? Oh yes, so I tried to get this job and the Mi Amigo sank and they couldn't find a Caroline, a Caroline, Seagull, Mi Amigo dj, except... muggins here. So they offered me a fair... a large amount of money in those days, I mean, for me anyway. I thought, there's about 400 quid to go in there and tell the story of what life was like on the boat, which I did for about an hour, and then they sliced it up and dropped it into news programmes and they did a documentary, a half hour documentary on the Mi Amigo, and the Caroline, Seagull and so forth. So the next day I thought, this is great, I'm a winner here, I've gotta get on, they've gotta give me a job now. So I called them up the next day... and they told me to Piss Off again! So... A friend of mine was running a club called Dingles in Camden Lock and I went along there and got a job as a dj, doing live stuff, which I hadn't really... done live dj work very much. I'm, you know, I'm a radio guy, but it was fun and I got, I'd done a bit of engineering on... for bands... in my, on my shows in the states. I used to have live music on my shows, so I knew roughly my way around a mixing desk and started to mix at the club, and that's how my sound engineering career took off. You know, within three years of that I was on the road. And as a sound engineer, again I got frustrated with the tour managers, you know, so I learnt how to do that... and then I got, when I was, became tour manager and a sound engineer I became frustrated with the agents, I learnt how to do that, and the only thing I never started was a label again. You know, Revelation Records was the last label I had. I had, I put out a single in Los Angeles, that was '79, with a band called the Move, no it wasn't... damn, I can't remember the name, but anyway the label was called Warped Records, which I thought was quite cool.

MD: The postscript to the

story is Radio Seagull and Ronan O'Rahilly, Radio Caroline... BE:

Yeah, I suppose it is. MD: Tell us how you met Ronan?

BE: Well, I got a phone call. When I got back after my... after I was asked to leave America, I got a phone call from Ronan saying would I like to do a Geronimo type show on the boat, and the station was gonna be called Radio Seagull, and it was gonna be progressive, and we could pretty much play what we wanted to, and have the same sort of programming refinements that we had for Geronimo, and there was... none. (laughing) As the wind blew and as our brains took us is how we did it. And, I mean, Seagull was very shortlived. Hugh did one term, one tour out there. I think I did three. I mean, it was very shortlived, mainly because Ronan wasn't paying anybody. It was rather hard to get the money out of him, and the tours were supposed to be like three weeks on, one week off, but the weather was so damn bad out there, you'd be out there for sometimes six weeks. We'd be down to the last loaf of bread... and so on and so forth. But, those were magic days, y'know. The fact I was out on a boat was insane, it was an insane thing to do, but again, I was stupid enough and young enough to get away with it in those days. I remember coming off, the first time I came back from the boat, I thought I'd better learn how to swim because I hadn't, at that time, learned how to swim, and so I went to a swimming pool on my week off and threw myself in, literally taught myself to swim, so when I got back on the boat at least I could do something if it went down because it seemed to be threatening that all the time.

CB: The programmes with Seagull. Was it just you on your own, or were you

doing them as two man programmes? BE: No, we were, we were... no, we were actually on at different times, so we were... no the days of the Geronimo combined show were just Geronimo... and I used to do, again I used to, I started up this jazz and blues show, I used to do it between six and seven in the morning for some reason. I dunno, 'cause I was bored I suppose... we had this station, we might as well use the damn thing. Y'know, if someone was up in Holland or Germany, and tuned in, they'd hear this wild jazz stuff pouring out of the station... and that got quite popular, we got quite a few listeners on that one, y'know, I was quite pleased. But then again, it always has done - the same with the jazz show I've just started on the borderline site. There's not, that music doesn't get aired on the radio and also to mix it, I'm not trying to do a commercial version of it, it's just doing it for the love of the music and if anyone turned round and said to me we want you to do, you know, to do this jazz show, you need to play, you know, like Jazz FM type of thing, I wouldn't do it. I'd just go, "fine, no worries mate, I'll go and do something else, I can play my music at home"...

CB: Bob Noakes, have you read Bob Noakes book? BE:

No.

CB: (paraphrasing quote from the book) "Barry and Hugh hardly ever saw the

light of day" BE: Pretty much, or we'd see mornings when we were leaving the studio at sort of... As I say, a number of times I walked home, I couldn't get on that, I can't remember the number of the bus, but the bus used to go up to Mill Hill and I had to walk home.

MD

(prompts): I think that was Bob Noakes talking about your time on

Caroline... he was the engineer on there. BE:

That's right, that's right. God, you guys know more than I do!

CB: Do you remember Bob Noakes? BE: Vaguely, yeah.

MD: So the boat was a bit of a rust bucket?

BE: Definitely a rust bucket. Definitely a rust bucket, and how it... I mean, the chain, the anchor... got twisted as the tides turned it, and so it knotted, so it actually started to sink, and the engine wouldn't work, so they had to... Ronan had brought engineers in to try and get the engine going, and then he had to get a diver in to go down to find out like... 'three turns to the left, three turns to the right to untangle the damn chain'... because we were going down, we were sinking slowly, let's put it that way. (laughs) They were fun days.

MD: How was Ronan as a character? How did you meet him? BE: At his place in Chelsea. He just invited me over to talk about, you know, what I, did I want to get involved with, with... with Mi Amigo, and to do radio out there. I gave him, I said, "Look, as long as you don't tell us what to play, I'll go out there and do it."

CB: Did Ronan ever want to call it Geronimo? BE: Well, it was always... this was Loving Awareness time for him, and I think he actually wanted to call it Loving Awareness, which I was quite... again, in those days, I didn't give a toss. As long as I could get on there and play what I wanted to play and communicate with people I... the peripheral stuff didn't really interest me at all. I mean, I was that focussed in what I was doing as a radio presenter. You know, piles of records I'd take over there and I'd throw into the bottom of a fishing boat, and we'd get smuggled out of, of... from Scheveningen, in Holland, onto the boat. Then the boats would be going up and down like this and we'd have to chuck ourselves over with this sort of five foot gap between the two boats with a heavy swell. I remember all that, very distinctly... and get onto the boat and then the cabins were disgusting. We had a good chef but, I mean, he was cooking in the most extreme conditions. I remember inventing a toast, peanut butter and marmite and honey... That was a, that was a, that ended up being my staple diet when I was on that boat, because sometimes you just couldn't cook hot food. I mean, 'A', the stove would blow out, but there would, y'know it was pretty, pretty hairy seas out there we were in. We all had to do three hours watch, which… what we did, that's all we did, we watched. There's nothing we could do about anything... and this tanker came by... it was a still night, absolutely still night, and there were some beautiful still ocean nights out there and days... and I was on watch after my show, and suddenly the whole boat... it felt like we were tipping over, and this tanker which went on for about a mile and a half came within literally a few hundred yards of us. I mean, how they hadn't seen our - we DID have a light - I'm sure we had a light (laughing), even that I don't know.

CB: Any idea why it wasn't called Radio Caroline at the time? BE: No idea. I can't remember.

CB: Any idea why it was called Seagull? BE: Er, no.

CB: And, any idea why Geronimo was called Geronimo? BE: Oh, Geronimo was called Geronimo because you, because that's what they used to shout when they threw themselves out of an aeroplane. You used to see them shout Geronimo, and it seemed like, it's a thing of freedom when you threw yourself out with a parachute in the war... watching the war movies, they shout Geronimo as they leapt out, and that's how it came. Also, he was a bit of a rebel as an Indian chief, and we quite liked that. It was a good tie in, and finding Amazing Grace was another magic moment as well, that song, you know, finding that single was...

CB: Can you remember that moment? BE: It was just in a pile of singles that we were playing. We were trying to find a theme tune for the, for the... for the station... and we obviously had a lot to choose from and, but that one, as soon as we put it on - that was it. You know, the way it slowly comes out with a single guitar and builds and builds and builds and builds and builds and then drops down again, and funnily enough, we were quite upset when they were using it on, I think it was the Isle of Wight Festival, and they were playing it on there, and they'd sort of made it their signature tune. We were like a little annoyed by that, you know. So we bombed them. We hired a plane. Tony Secunda hired a plane, stuck one of the guys up there. Hugh and I of course were on the rebel, free side of the fence. We weren't inside, we were outside with the Pink Fairies and all the anarchist bands doing the free festival outside, y'know, and we saw the plane come over bombing, and millions of Geronimo leaflets were bombed all over, all over, all over the festival... (laughing) Oh, dear, dear, dear.

CB: Happy days. BE: They were... as I say, you could, you felt you could do anything, and it didn't seem to cost that much to do it. It was just a matter of time and, y'know, they were magic days

MD: Fantastic. Batteries gone, tape's just finishing, perfect timing. BE: Great guys...

END OF BARRY EVERITT TRANSCRIPT

Click on thumbnail image to read this

article: revised 021020 |

||

|

|

||

|

|

||